Neezer Skroob Chapter 2 - The Uncharitable Season

Carole of Mockery

No hearth would warm, no church would call,

The world had turned and mocked his fall.

He begged the stones, he begged the sky,

And learned that even grief can die.

The fog of that November morning never seemed to lift. It crept into the corners of Scrooge's home, into the cracks of his mind, into the ledgers that haunted him even when closed. He woke to it each dawn, thick against the window glass, and carried it with him through the hours like a second coat. The counting-house was no longer his. Bob Cratchit, once the clerk who dared not ask for coal, now commanded clerks of his own. Scrooge retained a title still, partner in name, but no hand on the tiller.

At first, he told himself the season would steady him. Christmas was near, and Christmas had saved him once before. Surely its warmth would not abandon him now. He called upon Fred, his nephew, seeking comfort.

Fred opened the door with cheer, but when he saw his uncle, the smile faltered. Behind him, the drawing-room glowed with firelight and laughter, cousins and friends raising glasses, a woman's voice rising in song. The warmth spilled out onto the step, then seemed to draw back, as if uncertain of its welcome.

"My dear uncle," Fred said, and glanced over his shoulder. The song faltered. Someone whispered. "What brings you here?"

Scrooge explained, voice low, of Bob's books, of his fear that he had been cheated. Fred listened, but his eyes darted toward the room behind, as if embarrassed to be seen speaking of such things.

"Perhaps it is a misunderstanding," Fred said gently. "Bob is a good man. You mustn't brood. Come in, Uncle, join us. Tell no one of these dark suspicions."

But Scrooge, hearing the laughter resume behind his nephew's shoulder, saw not welcome but tolerance. He declined. Fred pressed no further. The door closed, soft as a verdict. Inside, the music resumed.

The charities were colder still. Scrooge, who once astonished them with his sudden largesse, now found their faces tight with polite dismissal.

"We are grateful for all you have done," one said, folding his hands. "But Mr. Cratchit has become our principal benefactor. It is better you let him lead."

"Lead?" Scrooge spat. "He fattens himself on my gifts and calls it virtue."

The man coughed, uncomfortable. "It is not seemly to speak so, sir. London knows Bob Cratchit as a saintly patron. To say otherwise makes you... unwell."

The word clung to him. Unwell. He heard it again not three days later, in the nave of St. Sepulchre's, murmured between two women in black bombazine. They did not know he stood behind them, or perhaps they did not care. "Poor old Scrooge," one said. "Quite unwell, they say. Raving about ledgers and theft. The mind goes, in the end." They crossed themselves and moved away, leaving him alone beneath the vaulted stone.

Once, he had been hated for his cruelty. Now, he was pitied for his decay. Neither suited him. Both stung.

The house in Cornhill was sold. He told himself it was practical, nothing more, too large for one man, but the truth was he could not pay to keep it. He moved to a smaller lodging, then smaller still. Each time he packed his few belongings, he told himself it was temporary, that the tide would turn. But tides, like seasons, do not turn for men already drowned.

At Christmas, the bells rang across London, the same as ever. Scrooge wandered the streets, hoping for an invitation, a kind glance, even a familiar nod. But the people hurried past, collars raised against the cold and against him. Once, he had been feared. Once, he had been admired. Now he was nothing at all.

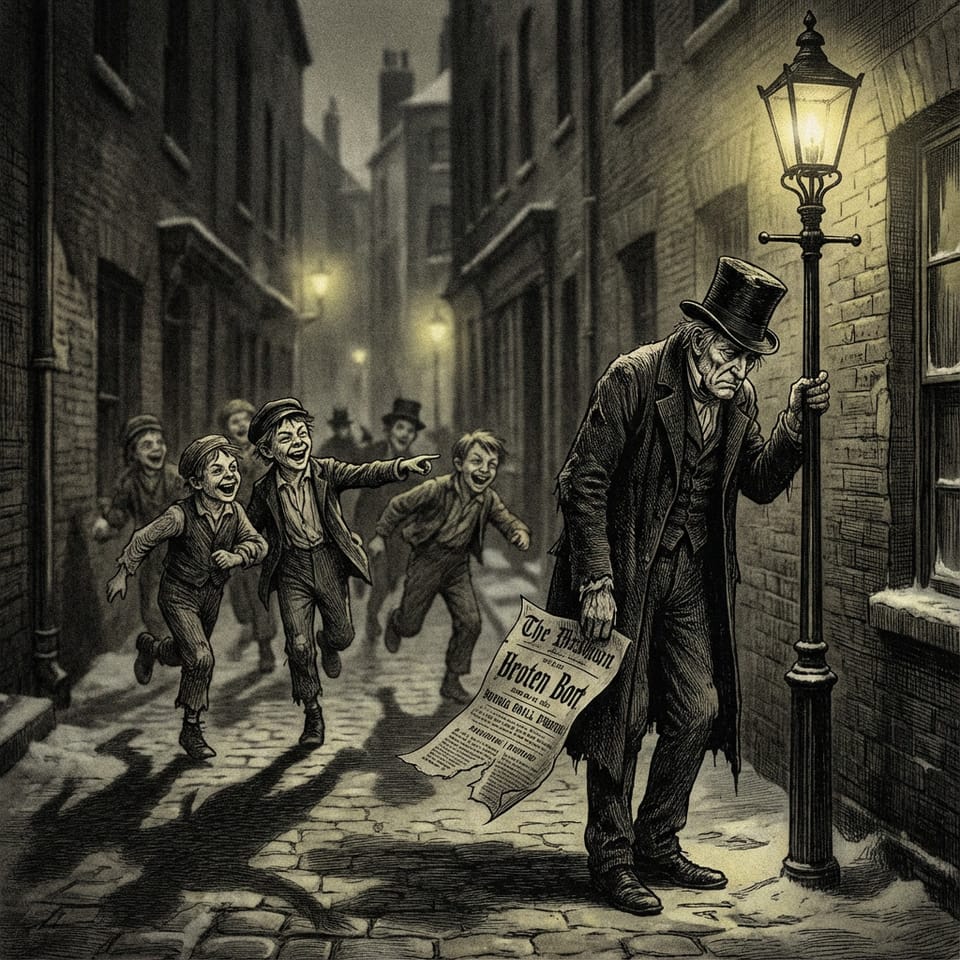

A group of boys ran past him, singing. He smiled faintly, expecting carols. But their song was twisted, cruel:

"Old man Scrooge has lost his crown, Bob took his gold and brought him down. Once he ruled, now beggars laugh, The miser's fortune split in half!"

They howled with mirth and vanished into the alley, their laughter echoing off the stones long after they were gone.

Scrooge leaned against a lamppost, his legs suddenly weak. The city itself had learned to mock him.

The letter came in January, when the frost still clung to the windows and the new year offered nothing new. His final lodging was to be vacated. Bob's signature sprawled across the bottom, bold as a king's decree: B. Cratchit, Sole Proprietor.

Scrooge read it thrice, the words burning hotter each time. Sole Proprietor. He could not decide which word wounded more: the arrogance of sole, or the theft of proprietor. He folded the letter carefully, placed it in his coat, and walked out into the frost. He did not return.

That night, he found himself on the Embankment, the Thames rolling black and wide beneath the moon. The water made no sound he could name, only a ceaseless muttering, as of secrets told and told again to no one. The cold rose from the stones beneath him and settled into his bones, patient as death.

Once, he had looked down from windows upon the poor, thinking them shadows against the river, shapes scarcely human. Now he was among them, shivering, coughing, clutching his thin coat close. A man beside him slept sitting upright, frost forming on his beard. No one spoke. No one asked another's name. They were past all that.

The city lights glowed gold in the distance, warm windows and bright laughter, but they were not for him. They had never, he understood now, truly been for him. He was no guest in warm parlors, no patron at rich tables, no miracle of Christmas. He was only Ebenezer, stripped of name, of fortune, of welcome.

As the bells tolled midnight, he closed his eyes. He thought of Marley's ghost, wrapped in chains of his own forging. And for the first time, Scrooge wondered if his own chains had been forged not of greed, but of generosity.